The only thing we have to fear is… fear itself.

The first inauguration of Franklin D Roosevelt

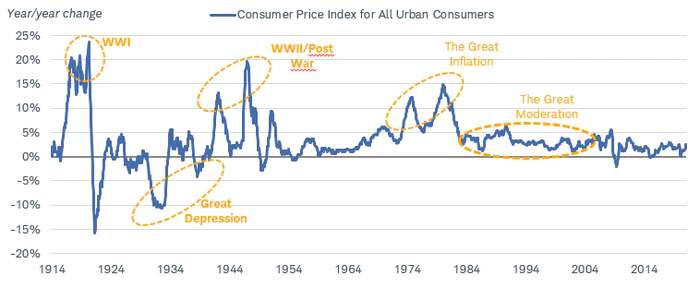

Much is being written in 2021 about price inflation, debating its persistent or transient nature, and conveying a general worry over the impact of inflation on asset prices. With this note, we hope to explore the history of inflationary periods to determine how much inflation impacts fundamentals and how much market action is merely fear itself.

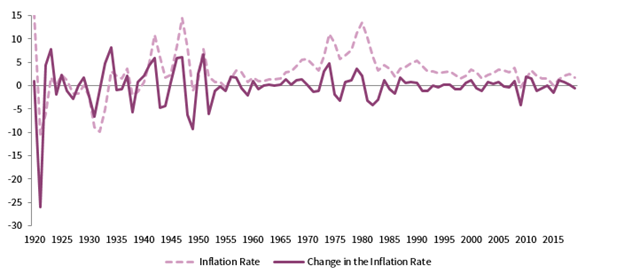

Investors with some age on them have been shaped by the period of elevated inflation in the 1970’s. As the graph below shows, most other inflationary periods have been associated with wars — with prices spiking from wartime shortages and then deflating when supply/demand conditions returned to balance. But the inflationary period of 1973-74 was different and not associated with wars but with monetary policy. Stock prices during this period declined by more than 45%, and bonds saw coupon interest undermined by declining principal value from rising rates.

Interestingly, the battle against inflation didn’t actually commence until after the Nixon Administration’s easy money policies had been abandoned and the Volcker Fed commenced a high interest rate regime to “break inflation’s back” in the early 1980’s.

Given the noise in the markets today, one would expect that this would have been a horrific period in which to be an investor. But despite persistent inflation during the ten years following the ’73-‘74 bear market, eight years were positive for equities. Bond returns were positive a similar percentage of the time. And shockingly, S&P500 returns (including dividends) averaged more than 15 percent per year during this decade. It would appear that inflation surprises are more important than inflation itself.

What does one make of this revelation, and how does it relate to private investments?

First, one must admit that market averages hide the volatility that affected many companies and sectors. Those bear market years were most difficult for high multiple growth stocks whose prices often declined by more than 80%. (Remember that Avon Products and Coca Cola were growth stocks of that era.) Clearly, future earnings are worth far less in a high inflation environment. Similarly, lower quality names with high leverage were also decimated as the rising cost of leverage took its toll on free cash flow and solvency.

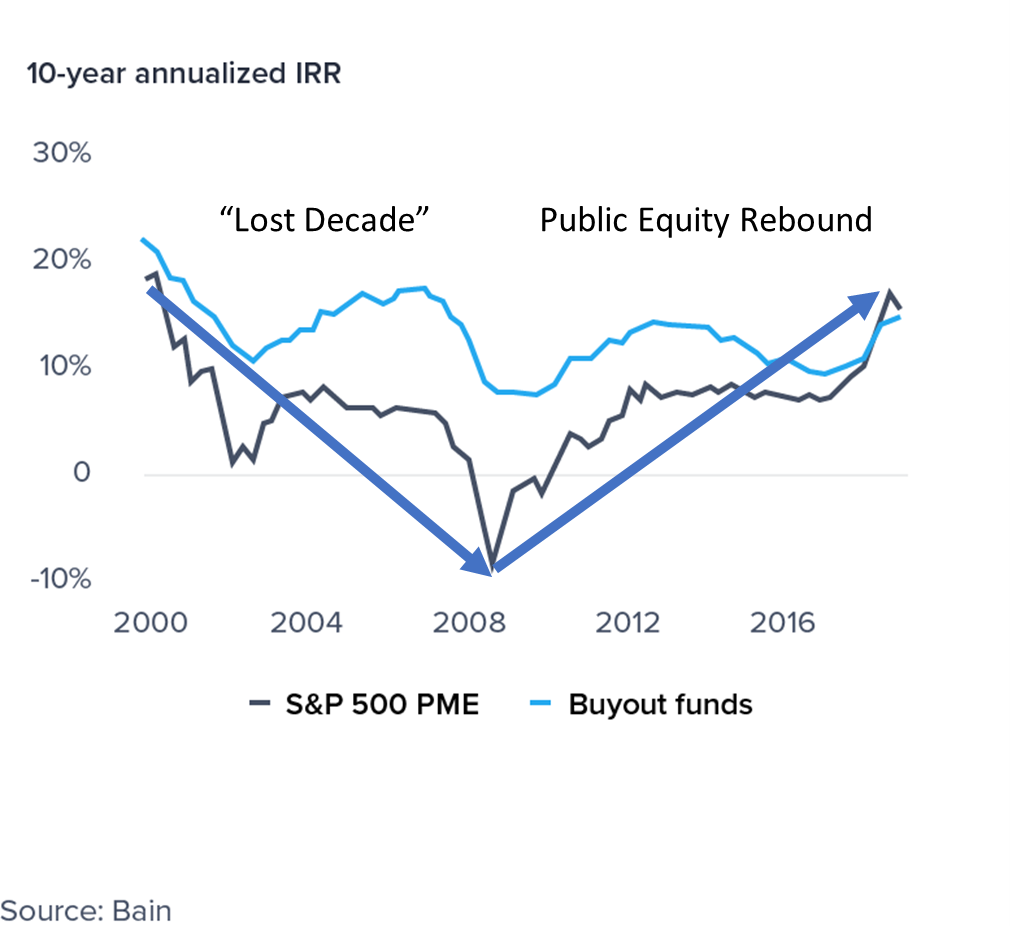

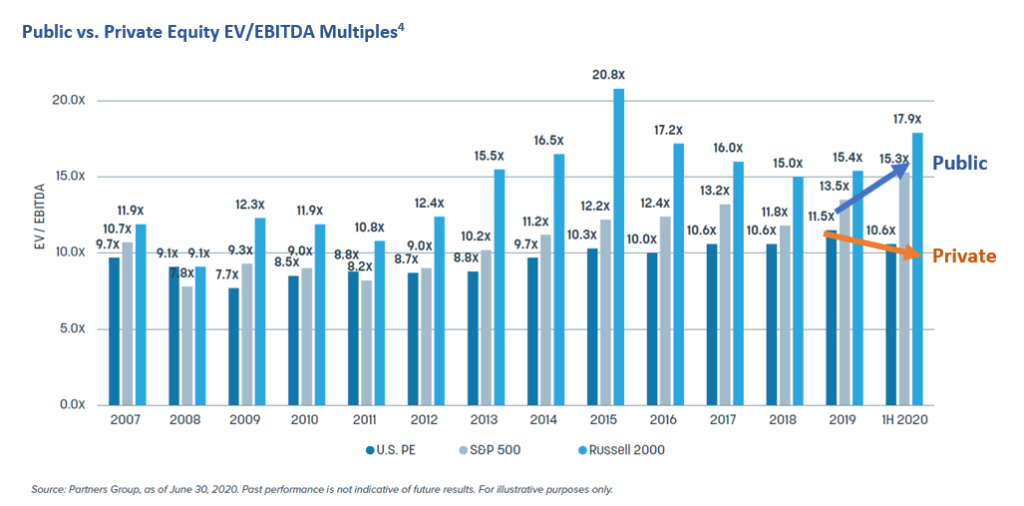

In the current era, the private equity industry has thrived in this period of lower cost leverage, allowing managers to widen their view of potential targets and buy at ever higher valuations. Assuming “real” rates of interest behave logically, then higher inflation would raise financing costs and put marginal deals out of reach. We would expect skilled managers to continue to succeed in such an environment, while those without an edge would eventually point their careers elsewhere. Investors without a coherent strategy may find this new paradigm less than accommodating.

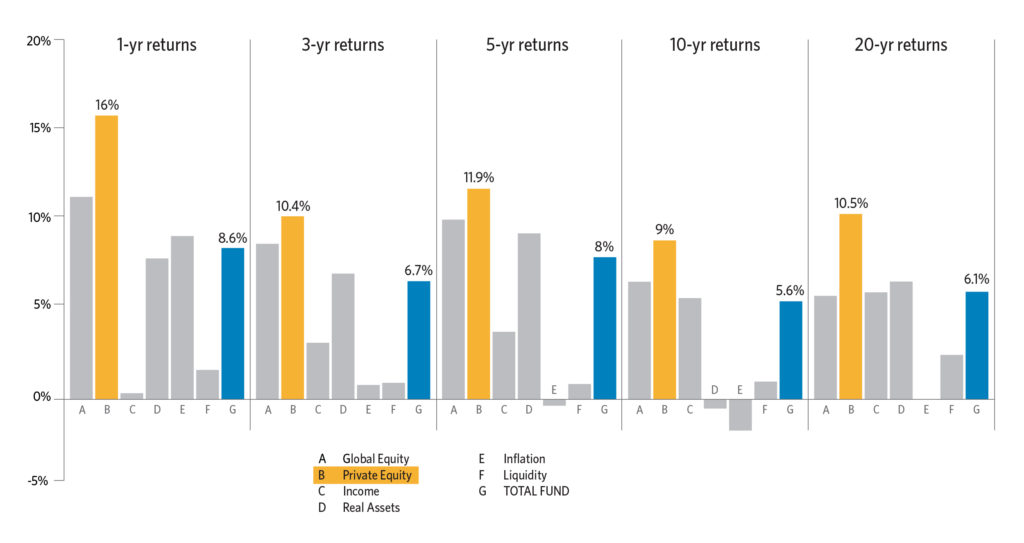

The takeaway for private investments, therefore, is not that inflation is scary, or that it is benign. The observation is that low leverage strategies should endure. Skilled managers and sponsors in private equity can continue to add value. Enterprises with pricing power will better be able to navigate whatever environment exists. And certain real estate categories are clearly inflation hedges, with rents that adjust over short time periods. Conversely, highly leveraged strategies and overpaying for growth are risky endeavors when discount rates rise.

At Altera, we strive to identify strategies with real value-added as opposed to “prosperity through financial engineering”. We seek enterprises with pricing flexibility and modest leverage. We favor durable revenue streams, even at the expense of being a little dull. We are long term investors in long duration assets.

We can’t predict inflation rates, or whether or not the current spike will endure or prove to be transitory. But as history has shown (in the graph above), change IS the constant, and inflation rates are just as likely to surprise on the downside as the upside. This makes the entire inflation discussion (for long term investors in private securities, anyway) as much a media-driven phenomenon as it is a fundamental one.